The internet of money

What is the internet of money? How will it work? Will it use central bank digital currencies, crypto dollars or Bitcoin? Or all of them?

The Berkshires is a popular countryside getaway in western Massachusetts, a few hours drive from New York or Boston. If you visit, you'll notice charming villages, verdant farms, and people using a currency other than US dollars. Berkshire County has its own local currency called the BerkShare.

BerkShares are available at local bank branches in exchange for US dollars at a rate of 95 cents per BerkShare. BerkShares can be spent at a rate of $1 to 1 BerkShare, effectively giving you a 5% discount for spending locally.

History is full of local currencies and hundreds are in use around the world. But most don't last for long. One of the most successful local currencies, the Bristol Pound, has been suspended and is converting all accounts to pound sterling.

New currencies are not as unusual as you might think. Currencies come and go all the time. Over the past few years we've seen many new digital currencies emerge. Like Bitcoin.

What's new is that central banks are entering the fray. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) estimates that 80% of central banks are now looking into central bank digital currencies. China has an active pilot and claims to have completed 4 million transactions, with a full roll-out planned for the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics. Other countries have also completed pilots.

Why is this happening?

Because money is becoming software. And the internet of money is emerging.

What is the internet of money?

It's the reimagining of money and the global financial system. It's doing for money what the Internet did for information. Like making payments as easy as sending email.

Central banks realize this, and it's making them nervous. What will the internet of money look like? How will it work? Nobody knows. But it's sure to be one of the most consequential developments of our lifetimes.

Let's start our exploration of the internet of money in an obvious place: central bank digital currencies. What exactly are they? What problems could they solve? What problems might they create? And should we be worried about China's?

One of the best and simplest definitions of central bank digital currency comes from the Bank of England:

A Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) would be an electronic form of central bank money that could be used by households and businesses to make payments. The key differentiation between reserves (which have been electronic and central bank issued for decades) is that they are universally accepted to all households. And unlike banknotes, would be fully digital.

Importantly, a central bank digital currency could enable direct peer-to-peer payments outside of today's banking and payment systems, and is money backed by the central bank (like cash) and held outside of commercial banks.

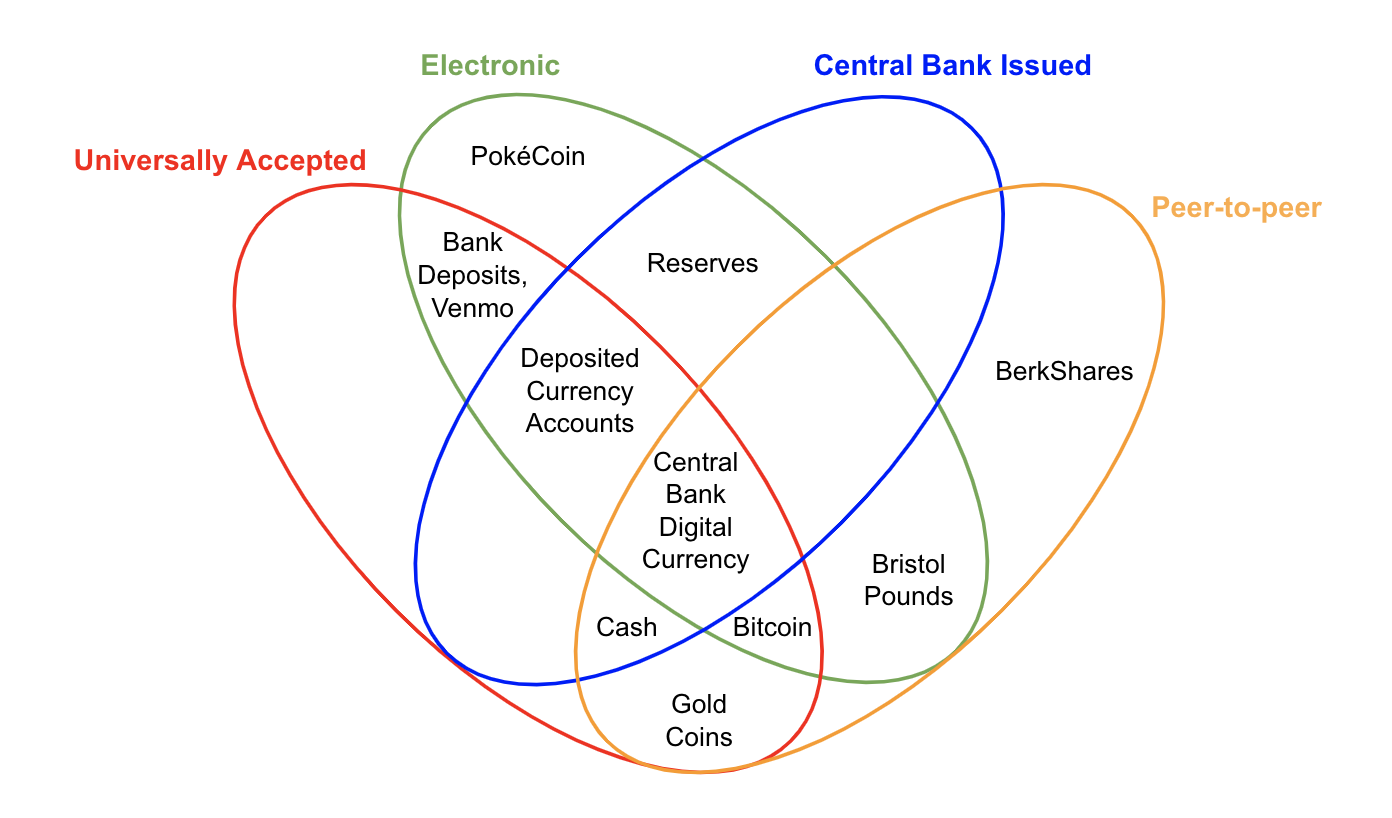

To help you understand how central bank digital currencies fit into the general monetary landscape, here's a "money flower" diagram based on the one created by the Bank for International Settlements:

The "money flower" categorizes money according to four properties:

- Is the money universally accepted or not? Note the diagram misses that this is a sliding scale and not zero or one. No money is acceptable everywhere.

- Does the money exist in electronic form?

- Is the money backed by the full faith and credit of the central bank? Cash and central bank digital currencies are, but bank deposits are not. That's why they need deposit insurance.

- Does the money exist in a form (whether physical or digital) such that it can be exchanged peer-to-peer with no intermediary?

With this understanding, let's look at the benefits central bank digital currencies might deliver.

Benefits of central bank digital currency

An increasing amount of work exploring central bank digital currencies is being done by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) and many others. Key benefits include:

Improved financial system stability: Some central banks are concerned about the concentration of payment systems among a few very large companies (some of which are foreign). Also, allowing settlement directly in central bank digital currency instead of bank deposits reduces the concentration of liquidity and credit risk in payment systems. This reduces the systemic importance of large banks.

Payments competitiveness: A central bank digital currency provides competition for large companies involved in payments, reducing the potential rents they can charge. It could also open the payments landscape to smaller players and reduce the need for small banks and non-banks to run their payments through large banks, which charge them high fees.

New monetary policy tools: A central bank digital currency enables much better data analytics on payment flows and could enable the central bank to deliver targeted "helicopter money" directly to people who need it as opposed to waiting for it to trickle down via the banking sector. An interest bearing central bank digital currency could also enable the central bank to force negative interest rates. That said, holding money that's explicitly reduced every month might not be that popular, and "helicopter money" could just as easily be delivered via FedAccounts—no central bank digital currency required.

Financial inclusion: Central bank digital currencies would be designed primarily for payments, whereas banks are primarily lenders. This is one reason bank's have such poor deposit and payment products. There's no incentive to improve them. Many central banks want to ensure a safe public money option is available in a world where use of cash is rapidly declining. However, the issue with the unbanked may be more complicated than it seems at face value. In the US, most of the 5.4% of people who don't have bank accounts don't want them because they don't trust banks. JP Koning discusses some creative ways this might be addressed via USPS accounts or even Walmart accounts. Could the same apply in other regions too? Could financial inclusion be addressed without a central bank digital currency?

Currency competitiveness: A central bank digital currency could expand global usage of a local currency and reduce the dependency on the dollar by improving payment capabilities. This could also help work toward reserve status.

Reduce the cost of cash: Supporting a national means of payment using cash has become very expensive in some countries, especially when they span large geographic areas or many small islands. A central bank digital currency could be a cheaper alternative.

Are central bank digital currencies the way the internet of money is likely to be built?

Problems with central bank digital currency

In theory, there are many good reasons to consider a central bank digital currency. But this is only in theory. In reality, the digital money landscape is moving very fast and the issues and challenges with a central bank digital currency are enormous.

First, there is the privacy issue. Unlike with cash, every single transaction could be recorded and monitored by the government. You might say people willingly trade away privacy for convenience today to use Facebook and Google. This is true. But the downstream impact of not using Facebook or Google is limited. And you can turn tracking off. But what if you couldn't buy or sell something because the government had decided to censor you or the other party? What if it was a mistake?

Second, central bank digital currency would be cancellable and could be remotely seized with the push of a button. Where would the checks and balances be on the safety of your money? Commercial banks at least have a financial incentive to protect their client's money and demand a court order to freeze an account. What incentives does the central bank have to protect your money? If there's a mistake, what's your recourse? Standing in line at a government office?

Third, a strong foreign central bank digital currency might make it harder for some countries to run independent monetary policies and control domestic financial conditions. And foreigners using local central bank digital currencies might similarly increase capital flow volatility and complicate domestic monetary policies.

Fourth, a central bank digital currency could disintermediate the banking sector and increase the possibility of bank runs. If individuals prefer holding central bank digital currency over bank deposits in any significant volume, banks will be forced to raise expensive wholesale money or increase interest paid on accounts. This will force banks to accept lower margins or charge higher interest rates on loans.

Finally—and most importantly—central banks are experts in money, not software. To understand how important this is, let's look at what's happening now at the intersection of software, networks and money.

The public blockchain is dollarizing

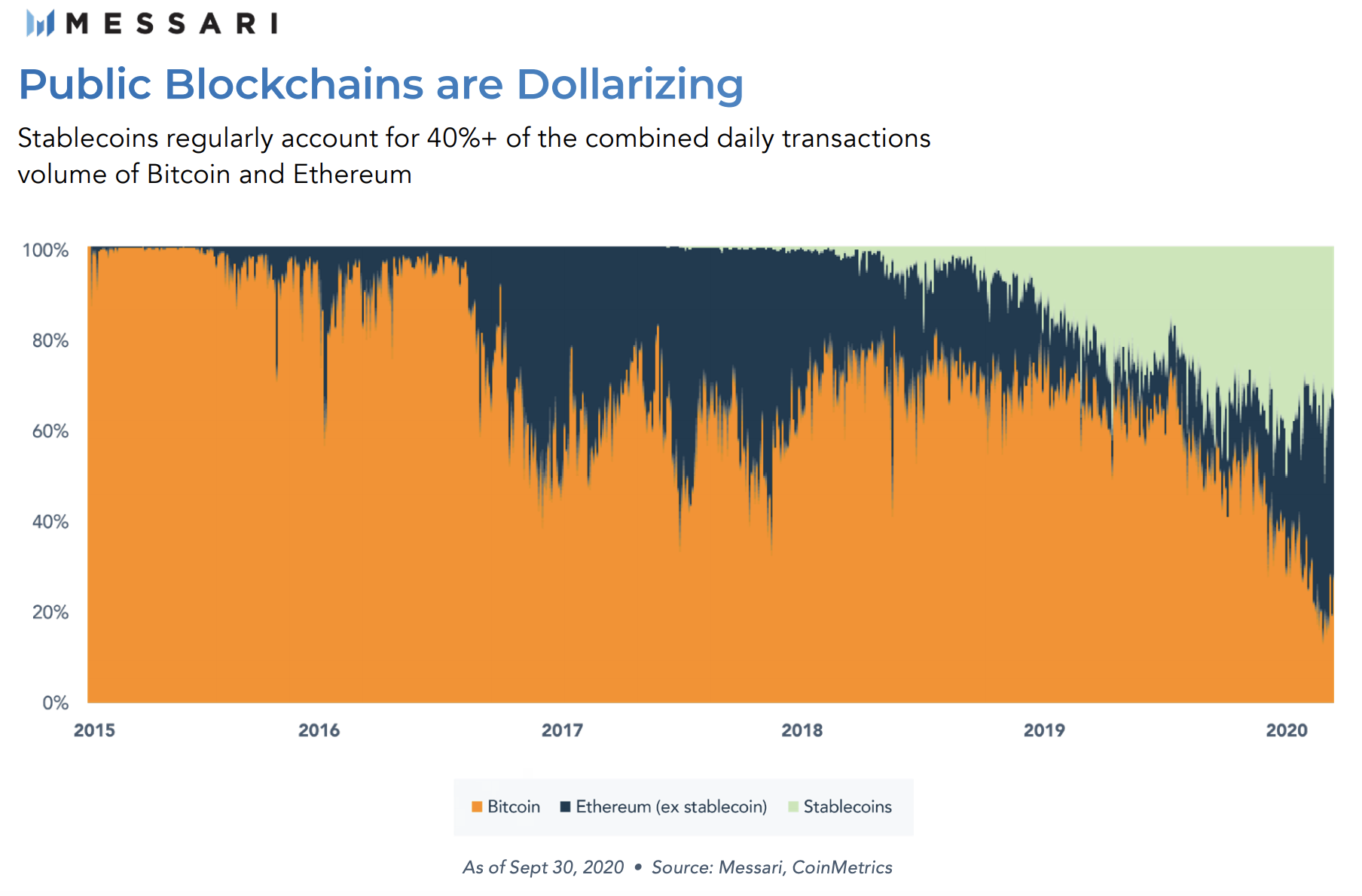

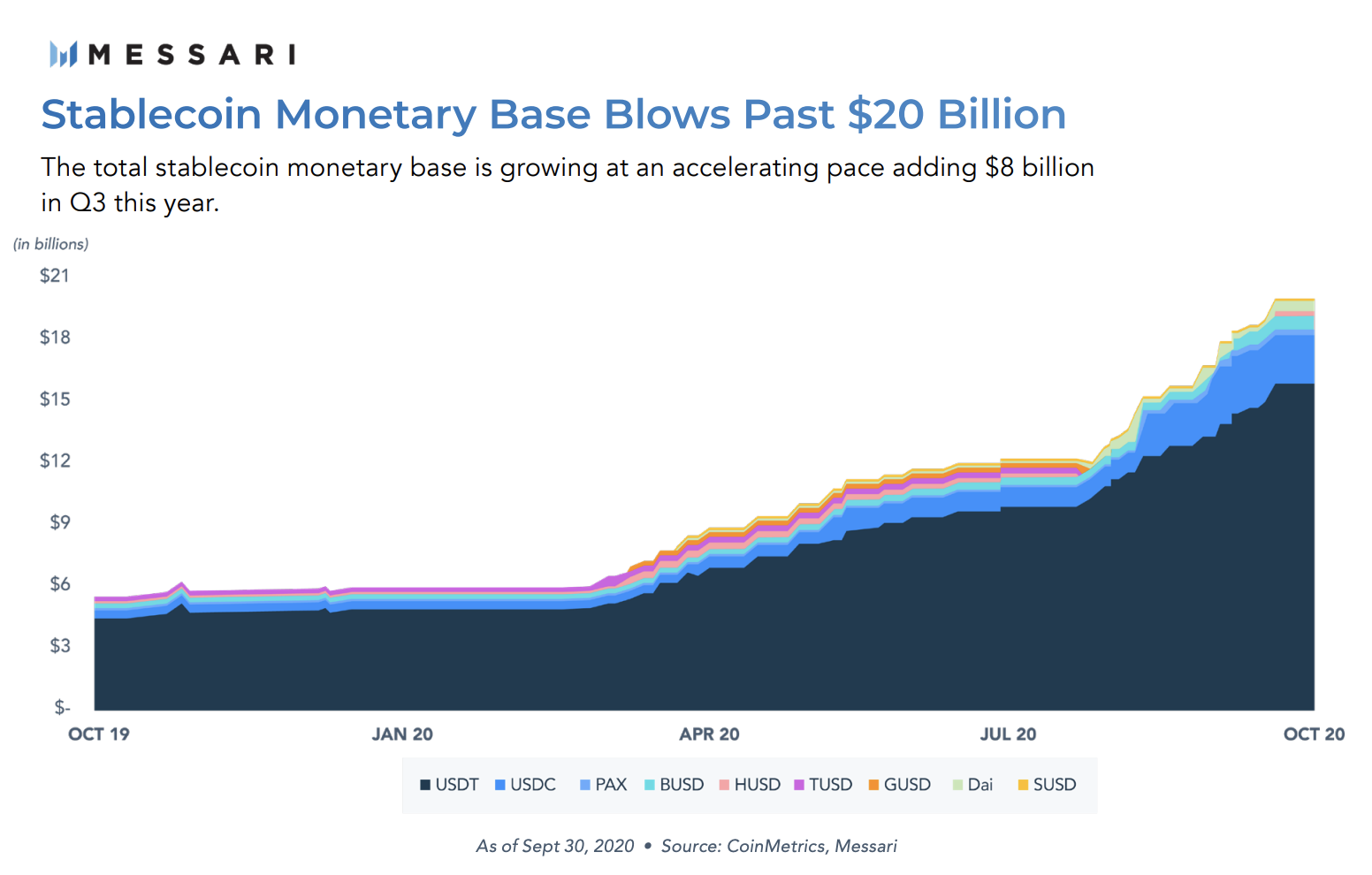

One of the most significant recent developments is that the public blockchains are dollarizing. Cryptocurrencies pegged to the dollar (called stablecoins) now account for 40% of the daily public blockchain transaction volume, up from almost zero two years ago.

In addition, the dollar denominated cryptocurrency monetary base is exploding, growing at over 300% this year. While only 7.5% of the monetary base of Bitcoin, crypto dollars are growing 50% faster.

Public blockchains dollarizing may be a pivotal development in how the internet of money will ultimately work. Why is it happening? And why so fast?

In short, a massive global supply-demand imbalance in the dollar market.

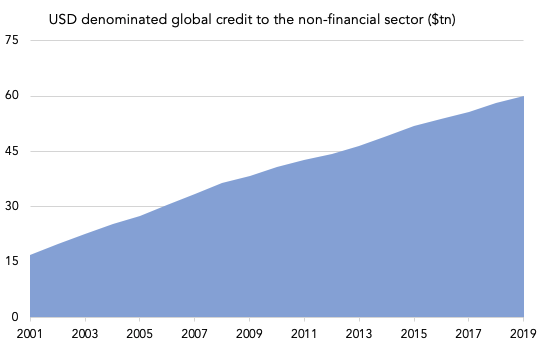

First, the world's debt today is largely denominated in US dollars, now reaching almost $60 trillion. Debtors require dollars to service this debt, and dollar debt is now 4x euro debt and 20x yen debt.

Second, while the fed funds rate is low, most developed country's rates are even lower. This drives demand for US debt, which again increases future demand for dollars to service this debt. Third, the US economy is stronger than most of its peers, driven especially by long term high returns from technology companies which require dollars to invest in. Fourth, the petrodollar system requires dollars for oil purchases. And finally, if US dollar debt continues to grow, central banks will have to add dollars to their reserves.

The global dollar shortage has enabled public blockchain crypto dollars to find product-market fit in enabling global economic actors to have a new way to access the dollar.

Public blockchains are competition for central bank digital currencies in delivering the internet of money, and the growth of these blockchains is exploding at the same time central banks are still at the drawing board.

Building the internet of money

The IMF published a report on Oct 19, 2020 on the macro-financial implications of digital money and hosted a major meeting of central banks in September. Meanwhile, Deputy Governor Tim Lane of the Bank of Canada called for urgency in developing central bank digital currencies.

Despite the talk, it's not clear that all these participants have a strong understanding of software, networks, and just how different network software money is from account-based money.

The electronic money the world has known to date has been account-based. An entry in someone's proprietary database. This electronic money is not software.

New electronic monies like central bank digital currencies, Bitcoin, or crypto dollars are not account-based. They are cryptographically secured asset nodes in a massively multi-client open-state database network. This electronic money is network software.

Building network software is very hard work, and creating the right incentives between participants so the network flourishes and scales is even harder.

Just ask Google. Their failed Google+ social network at one point had 1,000 Google engineers working on it. If 1,000 of the smartest engineers in the world could not build a social network people want to use, why do central banks assume they can build network software money people want to use? Understanding how auctions work is not enough to build eBay.

In fact, cryptocurrencies and central bank digital currencies are actually more difficult to build than most software (like social networks) because it is not easy to upgrade them or fix bugs once you've shipped. In this way, building network software money is more like building hardware than it is like building software.

You might say that Bitcoin and other cryptocurrency projects are open source. Perhaps central banks could just pick the elements they want and stitch them together? But being able to build a store does not mean people will shop in it. And linux being open source does not mean you can stitch together Amazon Web Services.

Is it really realistic to think that one or even a consortium of central banks will build and run TCP/IP for money? Or is this like the Department of Motor Vehicles deciding to build its own cars?

If central banks proceed with building their own network software money, it will likely cost much more than if done by the private sector and be only a fraction as good. More like the AppleTalk or IPX/SPX for money: networking standards that are now largely defunct.

It's worth looking back to the network protocol wars of the 1980s and 1990s and remembering how the adoption of the centrally planned Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) seemed inevitable in the late 1980s, only to be left in the dust by TCP/IP as Einar Stefferud, one of its chief proponents, gleefully pronounced: “OSI is a beautiful dream, and TCP/IP is living it!”

It would not be surprising if most central banks don't have a single person who's built and launched a new consumer software product, let alone one used by millions or billions of people. Building and launching the TCP/IP for money is not something you hire Accenture to do. It's far bigger than that.

As we talked about in software eats money, this is another case of the product (money) in an industry (central banking) becoming software. When this happens, every company (central bank) has to become a software company. And as a consequence, in the long run, the best software company will win.

The stakes are much higher with the internet of money than the internet of information. The dollarization of public blockchains is reinforcing dollar dominance.

Rather than rushing out a central bank digital currency or chasing crypto companies out of the US with draconian regulation, might America be better served by doubling down on protecting, funding and accelerating the cryptocurrency ecosystem that already exists?

Becoming the best software company for the Federal Reserve might be less about central planning and more about facilitating market forces to accelerate an ecosystem that is already reinforcing the dollar.

This could mean some self-disruption, but it might lead to the internet of money being an American phenomenon in the same way the internet of information was an American phenomenon.

What about China?

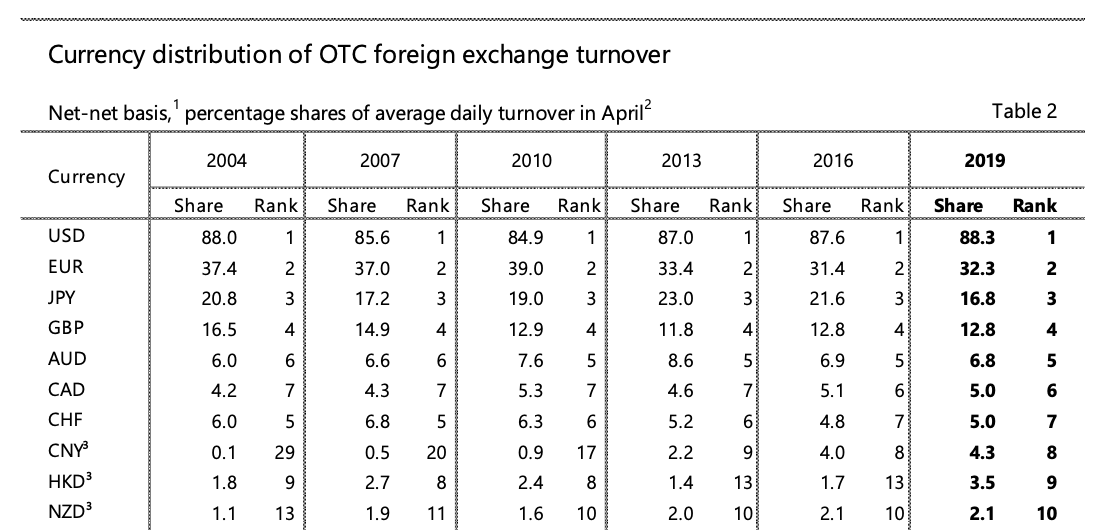

In terms of the yuan, it is nowhere close to replacing the US dollar, though it is growing fast. The yuan accounted for 4.3% of the 200% of over-the-counter foreign exchange in 2019, while US dollars accounted for 88.3% (each trade settles in two pairs so the total is 200% instead of 100%).

And in SWIFT's October 2020 RMB tracker, the yuan accounted for 1.97% of global payments by value whereas USD accounted for 38.45%.

From this position, China's central bank digital currency is unlikely to be disruptive on the global stage. If anything, it's more like the first version of the Great Firewall applied to money. It's worth noting that there are more cryptocurrency users in China than in any other country, despite the fact that it is illegal. China's central bank digital currency is for censorship and control of Chinese citizens at home and abroad. It's unlikely to get much adoption beyond its borders. Which Chinese trading partner wants to adopt cancellable digital Chinese money?

What about Bitcoin?

While a digital yuan might not change the yuan's competition with the dollar, Bitcoin is a different story. We've talked at length about Bitcoin as a product and why Bitcoin might be bigger than you think.

Bitcoin is an excellent store of value—likely the best the world has ever seen. But like gold, it's volatile, and so a poor unit of account today. No one wants to be paid in a currency that fluctuates in value plus or minus 50% month-to-month. A new financial system similarly needs more price stability, which is why these activities are taking place with crypto dollars today and not with Bitcoin directly.

But unlike dollars, Bitcoin has a well known and pre-programmed monetary policy that cannot change. It's politically agnostic. It cannot be debased the way the dollar is, and its use does not perpetuate cheap borrowing in America subsidized by the rest of the world.

Stablecoins are already using the global demand for dollars to solve their network cold start problem: the chicken and egg problem every new network faces to get off the ground. The protocols these cryptocurrencies use are multi-sided networks with increasing returns, which means their growth rates will become exponential. This may start a flywheel reinforcing global dollarization and making it very hard for competitors—like central bank digital currencies—to catch up.

Exponential growth always happens faster than anyone expects. Could central banks and the IMF be caught flat-footed and fumbling the same way the World Health Organization and Center for Disease Control were during the Covid-19 pandemic? Paul Graham, founder of Y Combinator notes, "I've never met anyone with a gut feel for exponential growth. You always have to calculate it. But everyone in the startup world at least knows never to turn their back on it."

If we enter a phase of hyper-dollarization, central banks will face a choice to compete directly with their own network money (which may not be an option), accept increased dollarization, or adopt Bitcoin for settlement as the only neutral alternative. Bitcoin does not have to be used for consumer payments or adopted as a consumer unit of account for it to become an integral and permanent part of the financial landscape.

What if Bitcoin became a global reserve currency as an international response to hyper-dollarization?

It remains to be seen how the internet of money will ultimately look. But what's clear is that it's bigger than the internet of information. It impacts much more than media and telecom companies. It impacts entire economies.

And could be destabilizing.

It impacts every single person in the world who uses money.

My hope is that if the internet of information could grant all of humanity access to the world's knowledge, maybe the internet of money can do the same for opportunity and wealth.

Did you like this article? Subscribe now to get content like this delivered free to your inbox. Learn more about what I do: https://andyjagoe.com/services/

- Cover photo by Valeria andersson

This newsletter is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. This newsletter may link to other websites and certain information contained herein has been obtained from third-party sources. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, Software Eats Money has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation.

References to any companies, securities, or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services.

Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Content in this newsletter speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others.