Can bitcoin compete with the dollar?

Bitcoin could become a reserve asset, but you're not likely to see stores pricing in bitcoin. Different types of money do different jobs.

Bitcoin has been on a tear lately. Trading volumes have greatly exceeded PayPal's expectations since they enabled Bitcoin for their 286 million users, corporate treasuries and university endowments are now holding bitcoin, and even long naysayer Ray Dalio has finally said it's a maybe.

I wrote that bitcoin will be bigger than you think. And this remains true.

But how big could it be?

If you're evaluating an early stage investment, instead of thinking about all the reasons it can't work, you learn a lot more by trying to imagine a future world where it does. You then ask, what has to be true for this to happen?

We've talked about price targets for bitcoin as a store of value asset. Premium subscribers can read the investment perspective here. But could Bitcoin be something much larger than digital gold?

To answer this question, we will imagine a future where you have a bitcoin bank account, get paid in bitcoin, and the stores you shop at price in bitcoin.

Is this possible? Could this state of the world actually happen?

Probably not. But maybe not for the reasons you think.

Today I will try to explain why.

It has to do with the jobs bitcoin does. Not all money does the same jobs. In fact, doing certain jobs well can necessarily mean doing other jobs poorly. This distinction is hard to see in daily life, and so it's easy to underestimate and overlook these differences.

Storing value

The job that gold and bitcoin do best is store value. You might think the dollar is pretty good at storing value. And if we're talking about a period of weeks or months then this is true. The dollar's purchasing power changes little month-to-month. And gold and bitcoin's purchasing power can vary significantly.

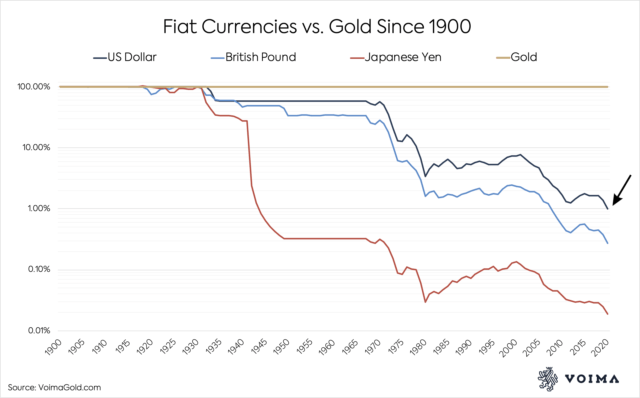

But if instead of looking month-to-month you look year-to-year or decade-to-decade, a different picture emerges. For anything other than the short term, fiat currencies have all been terrible stores of value.

Inflation has caused the purchasing power of the dollar to decrease 99% versus gold since 1900, and the pound and yen have done even worse. If you locked $100 of notes and $100 of gold in a vault in 1900, when you opened it in 2020 your gold would purchase 99 times more than your $100.

Why has this happened?

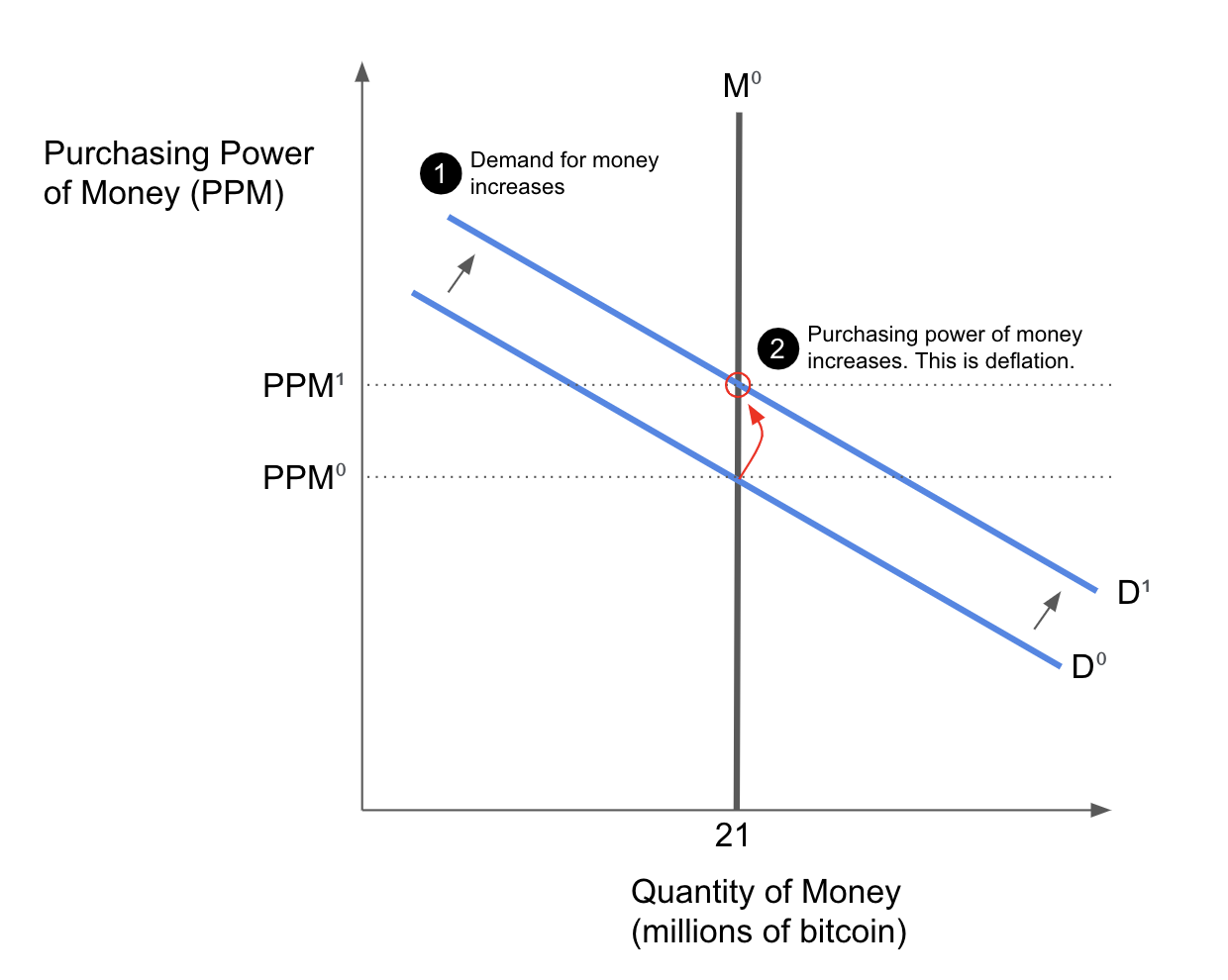

The price of gold is determined by supply and demand. The supply is fixed and increases at only 1.5% per year. Two critical factors in the demand for gold are global wealth and global population. Global wealth and population have historically increased faster than the supply of gold. So long as this is the case, gold's purchasing power will continue to go up. Meaning, the same amount of gold will buy more goods and services today than it bought yesterday. This is the definition of deflation. Getting more for less.

Bitcoin is the same.

Fiat currencies, by contrast, have had the supply of money increase faster than demand. So long as this is the case, the fiat currency's purchasing power will continue to go down. Meaning, the same amount of fiat currency will buy fewer goods and services today than it bought yesterday. This is the definition of inflation. Getting less for more.

Why do fiat currencies do this? Why do they steadily lose value over time?

Mediums of exchange, units of account

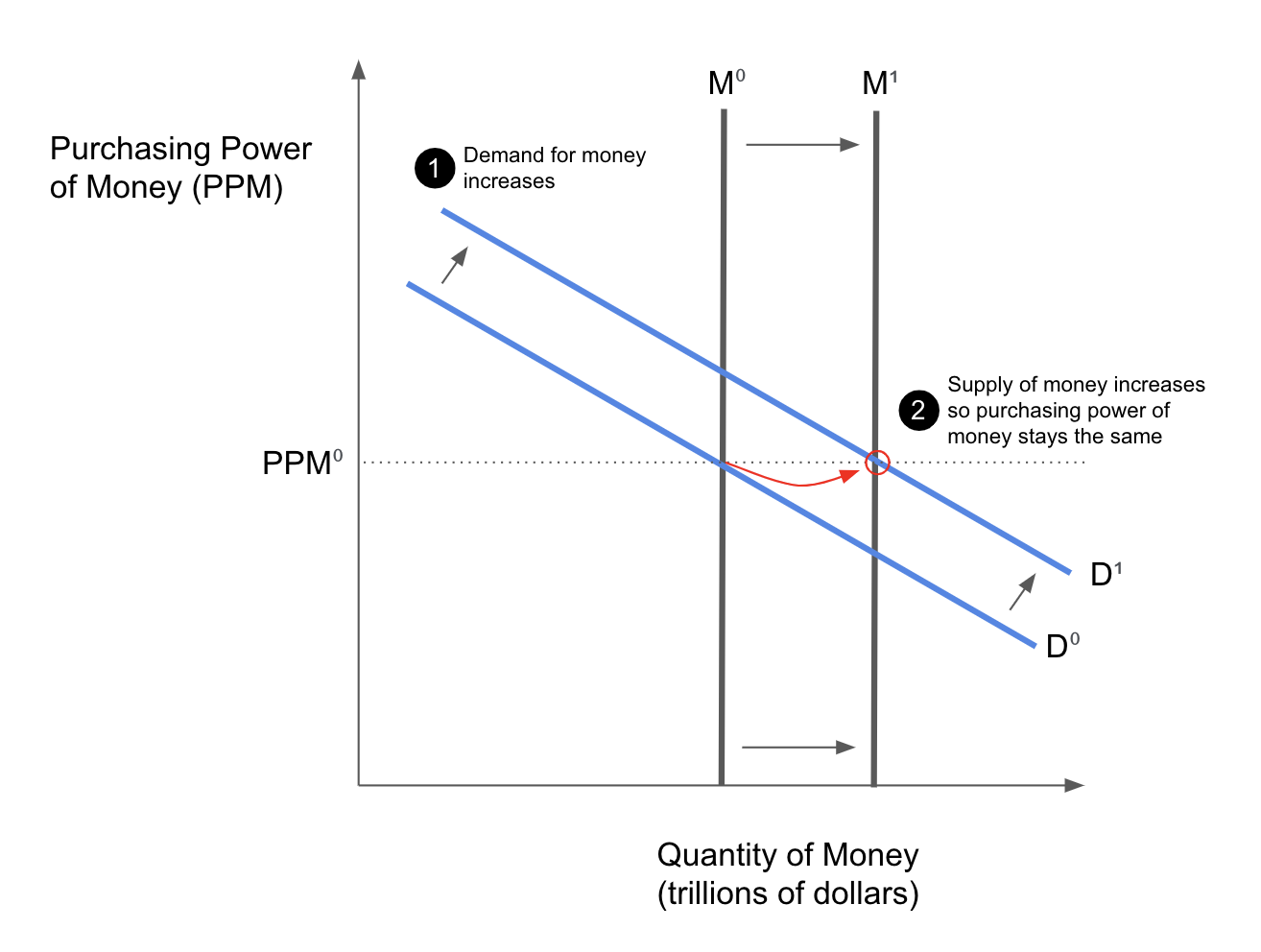

Central banks do not optimize fiat currencies to be stores of value. They optimize them to keep purchasing power stable, the most important job they try to do, since unstable purchasing power causes massive dislocation and friction in an economy.

How do you keep purchasing power stable? You adjust the supply of money to meet increases or decreases in demand. This is a very difficult job, because so many things affect the demand for money: changes in population, changes in productivity, credit boom and bust cycles, and many others.

The more stable purchasing power is, the better the fiat currency is as a medium of exchange and unit of account. This is the job fiat currencies like the dollar, pound and yen are optimized for. And what they do best.

A fixed money supply like gold and bitcoin have means dramatic changes in purchasing power as a response to changes in demand. This is why gold and bitcoin can be volatile in the short run, but the simple math of global growth ensures a consistent up and to the right trend in long term purchasing power.

In the same way that Milton Friedman said "Inflation is a monetary phenomenon arising from a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output³," the inverse is true as well. Deflation is a monetary phenomenon arising from a less rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.

A fixed supply of money necessarily means the purchasing power of money is not stable unless there is zero change in the demand for money. But this is not how the world works. The demand for money is constantly changing.²

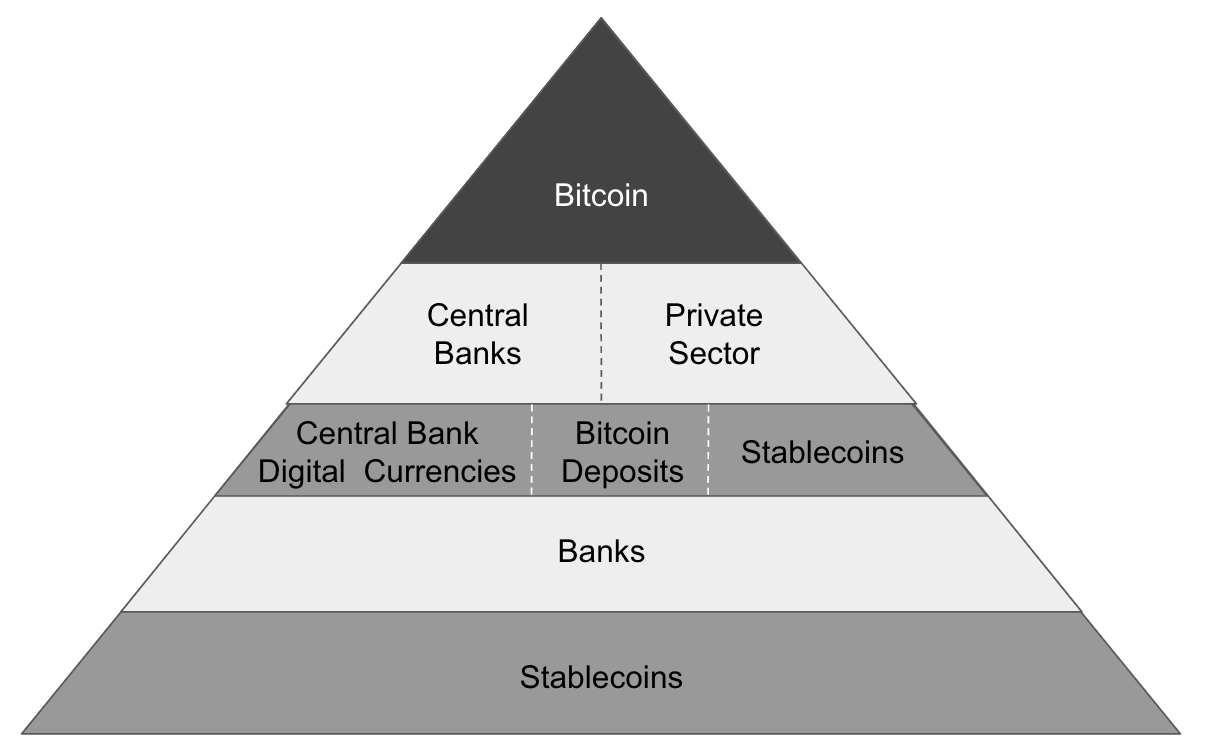

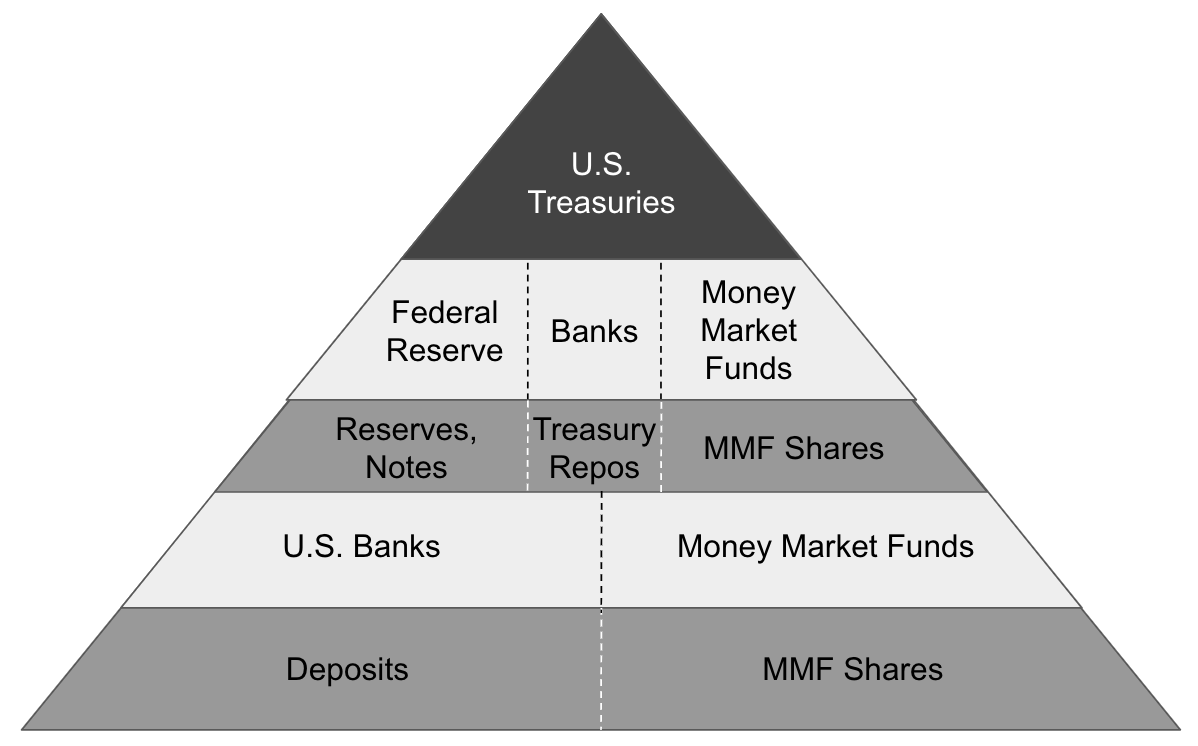

One possible answer would be for central and commercial banks to engage in fractional reserve banking with bitcoin. This would allow the supply of bitcoin to expand beyond 21 million in the same way banks create money today. By making loans.

But if this happens, how does a national economy insulate itself from global changes to demand and supply of bitcoin? Wouldn't it be better for bitcoin to be a reserve currency and have prices and salaries denominated in a stable currency whose purchasing power can be kept constant?

We touched on this idea in what everybody ought to know about money when we talked about Nik Bhatia's layered money pyramid:

Holding funds you need to spend in the next month or even the next year in a bitcoin account is high risk because the purchasing power of the money is volatile, even though it consistently trends up and to the right. Checking accounts and even "rainy day" savings accounts should be kept in a stable currency or stablecoin.

This tells us the idea that a future world where you get paid in bitcoin and the stores you shop at price in bitcoin is unlikely to materialize.

OK, but if central banks want to keep purchasing power stable, why do they target 1-2% inflation? Why not 0%? Or negative 1-2%?

Because as bad as inflation is, deflation is worse.

To fully dispel the notion that one day people will be paid in bitcoin and stores will price in bitcoin, we need to take a look at what happens in a world with deflation.

The problem with deflation

Adjusting the money supply to hold purchasing power stable is difficult and error prone in the best of times. The reason central banks target 1-2% inflation for their currencies is because most people prefer slight inflation over slight deflation.

Why?

Milton Friedman describes the widespread deflation that happened in the 1890s in his book Money Mischief³:

the price decline produced great dissatisfaction both in the United States and in the rest of the gold-standard world. The reason is partly what economists call “money illusion,” the tendency of individuals to pay primary attention to nominal prices rather than to real prices or to the ratio of prices to their incomes. Most people receive their incomes from the sale of a relatively few goods or services. They are especially well informed about those prices, and they regard any rise in them as a just reward for their enterprise and any fall as a misfortune arising from forces beyond their control. They are much less well informed about the prices of the numerous goods and services they buy as consumers and are much less sensitive to the behavior of those prices. Hence, there is the widespread tendency for inflation, provided it is fairly mild, to give rise to a general feeling of good times; of deflation, even if it is mild, to give rise to a general feeling of bad times.

Let's imagine an economy with 2% annual deflation. Each year, prices go down an average of 2%. This doesn't sound so bad, until you realize that this also means that every year you get an annual salary reduction of 2%. If you meet expectations. Also, your company has to lower their prices each year by 2% or be uncompetitive.

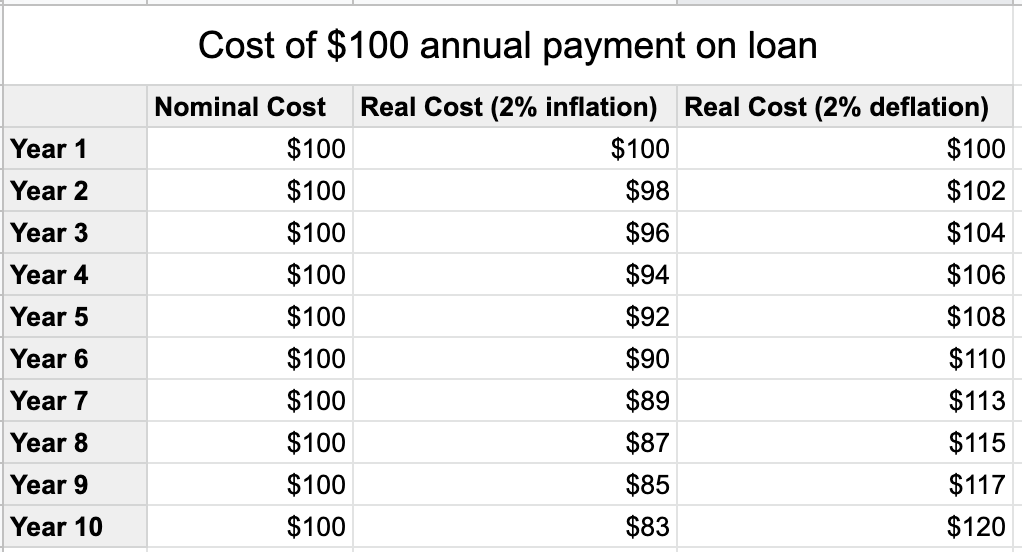

If that sounds uncomfortable, wait until we look at loans. The modern world is built on credit, and debt levels have never been higher. Inflation makes all these loans cheaper over time. But deflation makes them more expensive over time.

Imagine if the last payment on your 30 year mortgage was the most expensive one of all? Instead of the cheapest?

Under today's model of fixed repayment contracts and inflation, lenders factor inflation expectations into sophisticated models and internalize this as a cost. This works because the relationship between lenders and borrowers is asymmetric. Lenders have many loans and amortize costs across a stream of new loans and re-financings.

In a world of deflation, the increasing cost of debt is something that borrowers have to internalize. Unlike lenders, borrowers typically only have one or two loans. They are also less sophisticated in their ability to understand how the real cost of their loan will increase over time.

A deflationary currency punishes borrowers, rewards lenders and requires re-writing payment contracts worldwide. Can we trust lenders to provide fair loans that are in a consumer's best interest?

Finally, a strange thing happens when people expect money to get more valuable over time. Instead of spending it, they tend to hoard it.

Imagine you are considering a large purchase. If you expect the purchasing power of your money to be greater next month than this month, you have an incentive to wait. Since your spending is someone else's income, deciding to wait means that seller gets paid next month instead of this month. And when everyone is doing this, it sets off a contractionary chain reaction across an economy.

On the flip side, one benefit of a slight inflation in a money is that it discourages people from storing capital in unproductive ways. Unlike the stocks and bonds you own which are being used by companies to build and grow, the gold bars in your safe and your bitcoin in the cloud do nothing for society unless you are lending it.

You might argue that, in theory, there should be no difference between a 2% inflationary economy and a 2% deflationary one. They are mathematically equivalent.

This might be true, but getting more feels better than getting less psychologically. And trying to change human behavior here is swimming upstream against a powerful biological drive.

Species from ants to humans have developed strategies to save in good times in preparation for bad. For thousands of years we've told our children Aesop's fable about the ant and the grasshopper.

It might have surprised you the way people are hoarding during the pandemic, but according to Stephanie Preston, a behavioral neurobiologist at the University of Michigan who has studied hoarding for 25 years, hoarding is a totally normal and adaptive response to the uneven distribution of resources:

Everyone hoards, even during the best of times, without even thinking about it. People like to have beans in the pantry, money in savings and chocolates hidden from the children. These are all hoards.

Most Americans have had so much, for so long. People forget that, not so long ago, survival often depended on working tirelessly all year to fill root cellars so a family could last through a long, cold winter – and still many died.

Similarly, squirrels work all fall to hide nuts to eat for the rest of the year. Kangaroo rats in the desert hide seeds the few times it rains and then remember where they put them to dig them back up later. A Clark’s nutcracker can hoard over 10,000 pine seeds per fall – and even remember where it put them.

Similarities between human behavior and these animals’ are not just analogies. They reflect a deeply ingrained capacity for brains to motivate us to acquire and save resources that may not always be there. Suffering from hoarding disorder, stockpiling in a pandemic or hiding nuts in the fall – all of these behaviors are motivated less by logic and more by a deeply felt drive to feel safer.

Of course, hiding nuts in the fall is not the same as saving for retirement. But it is human nature to always strive for more than last time. To always do better.

Is it realistic to believe "more is better" could become "less is OK"?

Conclusion

Bitcoin cannot be a good medium of exchange or unit of account precisely because it is such a good store of value. If it were the sole global currency, its fixed supply would mean the world would have to stop growing before purchasing power stabilized and deflation stopped.

Fiat currencies like the dollar that are designed to keep purchasing power stable have to increase the supply of money when output increases. This is precisely why they cannot be a good store of value.

No money can do both.

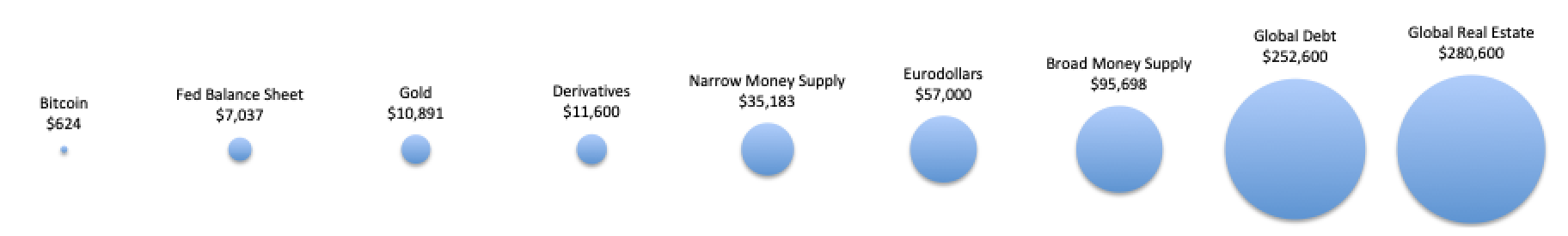

This is why Bitcoin's addressable market is an expanded financial store of value market. Not the $95 trillion broad money supply.

Understanding this is important to know when you should sell bitcoin.

But while bitcoin does not compete with the dollar to be the money you're paid in or the prices you see in stores, it might compete with the dollar in another way.

People talk about the dollar being the global reserve currency, but this is not exactly correct. The true layer 1 global reserve asset today is the collection of U.S. Treasury securities, not U.S. dollars. This is a subtle but important difference. Treasuries pay interest. Dollars do not.

Could bitcoin be a global reserve asset like U.S. Treasuries are today?

Maybe.

Bitcoin is a neutral asset and might be attractive to countries that want to reduce the local impact of U.S. monetary policy but still want a way to trade without having to worry about trust.

Will there be competition from other non-state monies?

Yes, perhaps.

And they might be even better.

But that will have to wait for a future article.

Did you like this article? Subscribe now to get content like this delivered free to your inbox. Learn more about what I do: https://andyjagoe.com/services/

- Cover photo by Bermix Studio

- Rothbard, Murray, The Mystery of Banking, Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2008.

- Friedman, Milton, Money Mischief, Mariner Books, 1994.

- Source - Bitcoin: Messari, Jan 22, 2021; Fed's Balance Sheet: U.S. Federal Reserve, July 2020; Gold: World Gold Council, May 2020; Derivatives (Market Value): BIS (Dec 2019); Narrow Money Supply: CIA Factbook; Eurodollars: BIS, World Bank, Rabo Bank; Broad Money Supply: CIA Factbook; Global Debt: IIF Debt Monitor; Global Real Estate: Savills Global Research, 2018

This newsletter is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. This newsletter may link to other websites and certain information contained herein has been obtained from third-party sources. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, Software Eats Money has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation.

References to any companies, securities, or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services.

Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Content in this newsletter speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others.