What is a crypto asset, anyway?

How crypto assets fit into Greer's asset superclass framework, how they accrue value and their distinct economic characteristics.

Public blockchain architectures and their native assets are well on their way to being the next great set of applications to leverage the Internet.

Many people call the native assets of these systems cryptocurrencies, but this can be misleading. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines cryptocurrency as:

Any of various digital payment systems operating independently of a central authority and employing cryptographic techniques to control and verify transactions in a unique unit of account; (also) the units of account of such a system, considered collectively.

This definition is quite broad and anchors around a payment system. But not all native assets are payment systems, and some native assets are consumed more like commodities than currencies.

Here's a more formal definition of cryptocurrency from Wikipedia:

A cryptocurrency is a system that meets six conditions:

- The system does not require a central authority; its state is maintained through distributed consensus.

- The system keeps an overview of cryptocurrency units and their ownership.

- The system defines whether new cryptocurrency units can be created. If new cryptocurrency units can be created, the system defines the circumstances of their origin and how to determine the ownership of these new units.

- Ownership of cryptocurrency units can be proved exclusively cryptographically.

- The system allows transactions to be performed in which ownership of the cryptographic units is changed. A transaction statement can only be issued by an entity proving the current ownership of these units.

- If two different instructions for changing the ownership of the same cryptographic units are simultaneously entered, the system performs at most one of them.

This definition is much more clear in describing unique attributes of these native assets, but still calls them cryptocurrencies. And doesn't take into account that different assets have different economic and investment characteristics. To account for this, it's more appropriate to describe these native assets as crypto assets than cryptocurrencies. We will do so from now on.

Today we're going to talk about what crypto assets are and how they accrue value. We'll focus on the economic characteristics that make crypto a unique and distinct investable asset class.

But first, we need a definition for what an asset class is, and a framework to relate asset classes generally. This is important to understanding how to value different crypto assets.

Asset classes

Robert Greer, vice president of Daiwa Securities, published "What is an Asset Class, Anyway?" in a 1997 issue of Journal of Portfolio Management and it is still widely referenced today.

In 2018, he published an update called "The Superclasses of Assets Revisited" where he clarified his original asset class definition:

a set of [investable] assets that bear some fundamental economic similarities to each other, and that have characteristics that make them distinct from other [investable] assets that are not part of that class.

The assets in a class have similar risk factors distinct from that of other investable assets. This definition looks at underlying drivers of change to the price of an asset. It does not require that assets in one class have a low correlation with assets in another class or that assets within the same class be highly correlated.

With that definition of asset class in mind, Greer defines three asset superclasses:

- Capital assets

- Consumable/transformable assets

- Store of value assets

Each superclass can be divided further into separate asset classes. Stocks and bonds are said to be different asset types, though both are capital assets.

Some assets have characteristics of multiple asset classes. For example, gold has characteristics of a consumable/transformable asset and characteristics of a store of value asset.

Let's look at each superclass in turn.

Capital asset

A capital asset is an ongoing source of something of value. One of the most well-known capital assets is stocks. They provide the expectation of a stream of dividends for an indefinite period of time. The other well-known set of capital assets is bonds, which provide the expectation of a stream of interest payments, ending with the return of principal.

Stocks and bonds both provide a stream of monetary rewards, and thus their value can be assessed using a discounted cash flow model to determine a net present value. When an investor's time value of money (discount rate) increases, the value of the capital asset decreases. When an investor's time value of money (discount rate) decreases, the value of the capital asset increases. The unifying characteristic of a capital asset is that it is valued based on discounted cash flows and is subject to changes in an investor's discount rate.

Consumable/transformable (C/T) asset

You can consume it. You can transform it into another asset. It has economic value. But it does not yield an ongoing stream of value… . The profound implication of this distinction is that C/T assets, not being capital in nature, cannot be valued using net present value analysis. This makes them truly economically distinct from the superclass of capital assets. C/T assets must be valued more often on the basis of the particular supply and demand characteristics of their specific market.

The best known C/T assets are physical commodities like oil, wheat, corn or copper. Some assets like corn are consumed directly. Other assets like oil are transformed into another asset (gasoline) that is then consumed.

The value of these assets is often accessed using the derivatives of commodity futures, but neither the underlying commodity nor its associated futures contract generates an ongoing stream of revenue. Therefore, these assets must be valued based on supply and demand and cannot be valued using a discounted cash flow model.

Store of value asset

[Store of value assets] cannot be consumed. They cannot be valued using a discounted cash flow model. Yet they do have value. Fine art is an example of the SOV asset superclass. While it does provide some non-economic value, it is still “worth something.” Currencies (distinct from debt or equity denominated in a foreign currency) is another example of where an investor may put his dollars (assuming the USD is his home currency) if he thinks that the foreign currency will appreciate relative to the dollar.

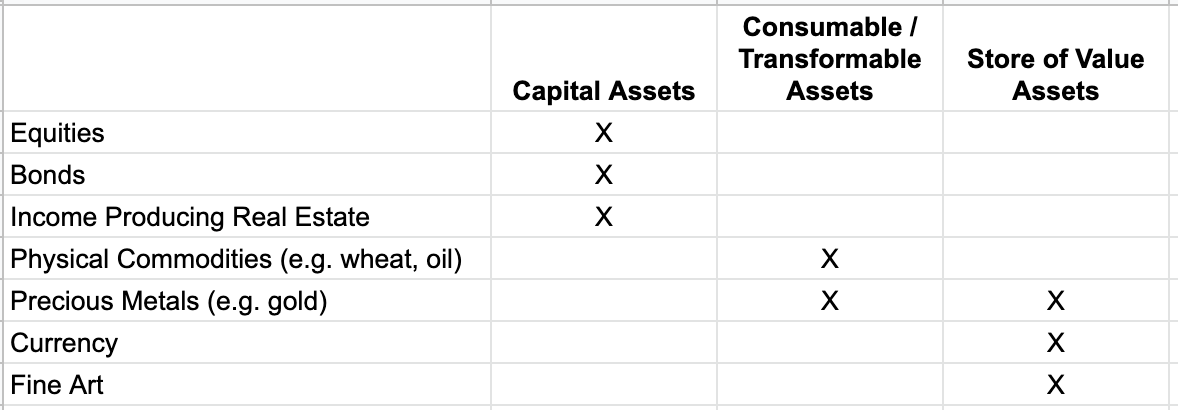

Below is a chart of traditional asset classes categorized by their superclass:

With this framework in place, let's return to crypto assets.

Crypto assets

One of the unique things about investing in crypto is that each crypto ecosystem is a multi-sided network designed such that value is captured by the ecosystem's native asset. A crypto asset is a native asset of a public blockchain ecosystem.

Companies working on new crypto projects typically allocate a portion of the project's tokens to themselves (subject to a vesting schedule) and sometimes sell another portion of the project's tokens to investors if they need to raise money. Then, once the project is ready, it is released to the community and the crypto asset is distributed using one or more common methods.

From this point on, the token can be bought and sold via a decentralized exchange like Uniswap or a centralized exchange like Coinbase (if and when it is listed).

Understanding how to value the token requires that we consider where the crypto asset fits into Greer's asset superclass framework:

Decentralized finance (DeFi) applications charge fees, and holder's of the native asset anticipate capturing value directly via dividends or through "token burn" mechanisms similar to stock repurchasing. Another example of a capital asset are non-fungible tokens (NFTs) representing digital land that is rented to players in a game.

Centralized exchanges like Binance provide a discount to customers who pay trading fees using their BNB crypto asset and "burns" tokens (reducing supply) on a periodic basis based on their business results (again, like a stock repurchase).

Digital commodities like Filecoin and Chainlink require the use of their native crypto asset to provide or consume the digital commodities they provision.

Currencies like BTC, the native crypto asset of Bitcoin, as well as stablecoins and digital fine art are all in the store of value asset superclass.

This being said, many crypto assets have characteristics of multiple superclasses, similar to gold. For example, ETH, the native asset of Ethereum, has characteristics of all three superclasses now that it is possible to stake your ETH and generate yield natively within the Ethereum ecosystem.

When assets and ecosystems are programmable, traditional lines and distinctions blur. Economic characteristics can even change over time as a crypto asset's ecosystem evolves.

Taken together, this has led many to conclude that crypto assets are a new asset class. As the depth and breadth of crypto projects expands and as our chart details above, you might even argue it's more than one.

How crypto assets are different

The analysis of crypto assets is similar to the analysis of traditional assets, but you must pay careful attention to the economic characteristics that make them different.

Chris Burniske and Jack Tatar in their book Cryptoassets describe four criteria for evaluation: governance, supply schedule, use cases and basis of value.

We'll look at each in turn.

How are they governed?

Assets are subject to governance, just as countries are. Cryptoassets describes three elements of governance for assets of all kinds: asset procurers, asset holders, and the regulatory body or bodies that oversee the behavior of procurers and holders:

For example, a typical equity has the management of the underlying company, the shareholders of the company, and the SEC as a regulatory overseer.

Energy commodities and their associated derivatives, such as oil and natural gas, are arguably more complex. The governance of the procurers is often much more dispersed and global in nature, as are the holders of the physical commodities. For the financial derivatives of these commodities, in the U.S. the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) provides a layer of regulatory cohesiveness, while the SEC plays the same role for ETFs, mutual funds, and other fund structures that are composed of these assets.

Currency, a somewhat more controversial asset class, also has a unique governance profile. First, a central bank controls its distribution, while the people of the country, global businesses, and international creditors often dictate the exchange rate and use of the currency (though a controlling nation can manipulate these arenas). Regulatory bodies vary by nation, and there are international regulatory bodies like the International Monetary Fund if the currency of a nation hits choppy water.

Crypto assets follow a unique model of governance, in many ways inspired by the open source software model. The procurers of the asset and its use cases typically starts with a core team of software developers who create a public blockchain protocol that uses the native asset. The software is open source, and new developers can earn their way onto the team by making valuable contributions.

But the core team is not alone in procuring a new crypto asset. This development team is also dependent on miners or stakers who own the computers that run the code. The miners or stakers also have a say in the behavior of the code because the developers can't force them to update their software. The developers have to convince them that new software makes sense for the overall ecosystem and their economic interests.

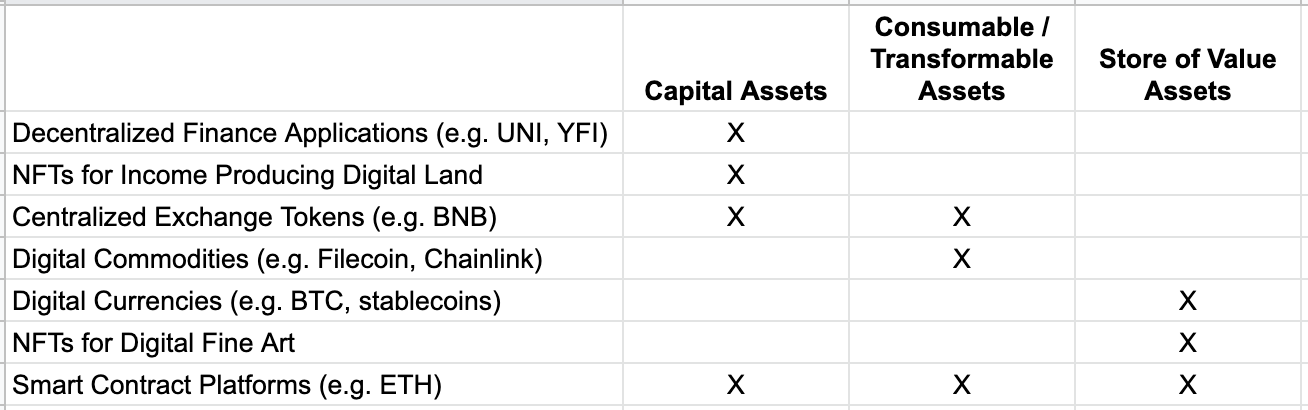

Below you can see the Bitcoin network ecosystem. Other crypto asset ecosystems are similar.

A third element of asset procurement are the third party companies that create the products that interface between the crypto asset and the broader community. These companies sometimes employ the core developers, but even if they don't they can have significant influence if they're important to user adoption.

Beyond procurers, the holders of the crypto asset are the investors who buy the asset as an investment or the end users who buy the asset for its utility in the underlying blockchain system. Procurers have a strong interest in listening to the feedback of the holders, because a decrease in usage will reduce demand for and price of the asset.

Finally, there is an emerging regulatory landscape to oversee the behaviors of procurer and holders.

What is the supply schedule?

Procurers typically have the strongest role in determining an asset's supply schedule, but all three elements of governance can influence it.

From Cryptoassets:

For example, with equities there is an initial share issuance via an initial public offering (IPO). The IPO helps the management of the underlying company raise cash from the capital markets and get broader exposure for their company’s brand. The company can continue to issue shares, via stock-based compensation or secondary offerings, but if they do so at too high a quantity, their investors may rebel because their ownership of the company is becoming diluted.

Bonds, on the other hand, are markedly different from equities. Once a company, government, or other entity issues a bond, that is a claim upon a fixed amount of debt. There is no negotiating on that debt except in the case of default. That same entity may issue more bonds going forward, but unless that issuance is an indicator of economic distress, typically a follow-on issuance of bonds will have little effect on a prior set of issued bonds.

Depending on the energy commodity, there can be varied supply schedules, though nearly all of them are calibrated to balance market supply and demand and to avoid supply gluts that hurt all procurers. For example, with oil, there’s the famous Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which has had considerable control over the supply levels of oil.

The central banks that control currency supply have even more control than OPEC. As the world has witnessed since the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009, a central bank can choose to issue as much currency in the form of quantitative easing as it wants. It does this most often through open market operations, such as buying back government issued bonds and other assets to inject cash into the economy. Central bank activity can lead to drastic increases in the supply of a fiat currency, as we have seen in the U.S. dollar.

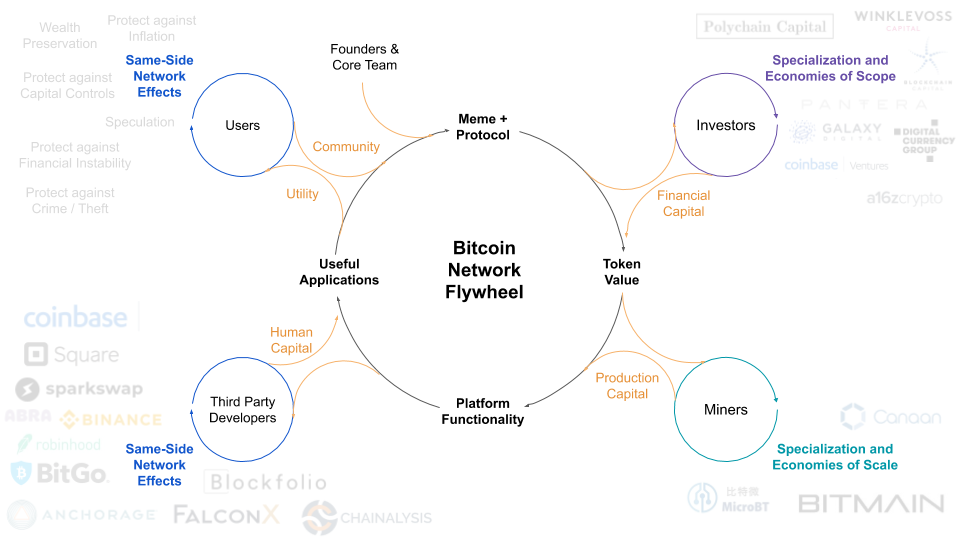

The supply schedule of crypto assets is typically metered mathematically. While a supply schedule is always set in a protocol from its genesis, it can change over time if a majority of networks participants agree and miners and stakers update their software.

Many crypto assets are constructed to be scare in their supply. Some, like Bitcoin, will be even more scarce than gold. Bitcoin has one of the simplest supply schedules. It has remained unchanged since its genesis block:

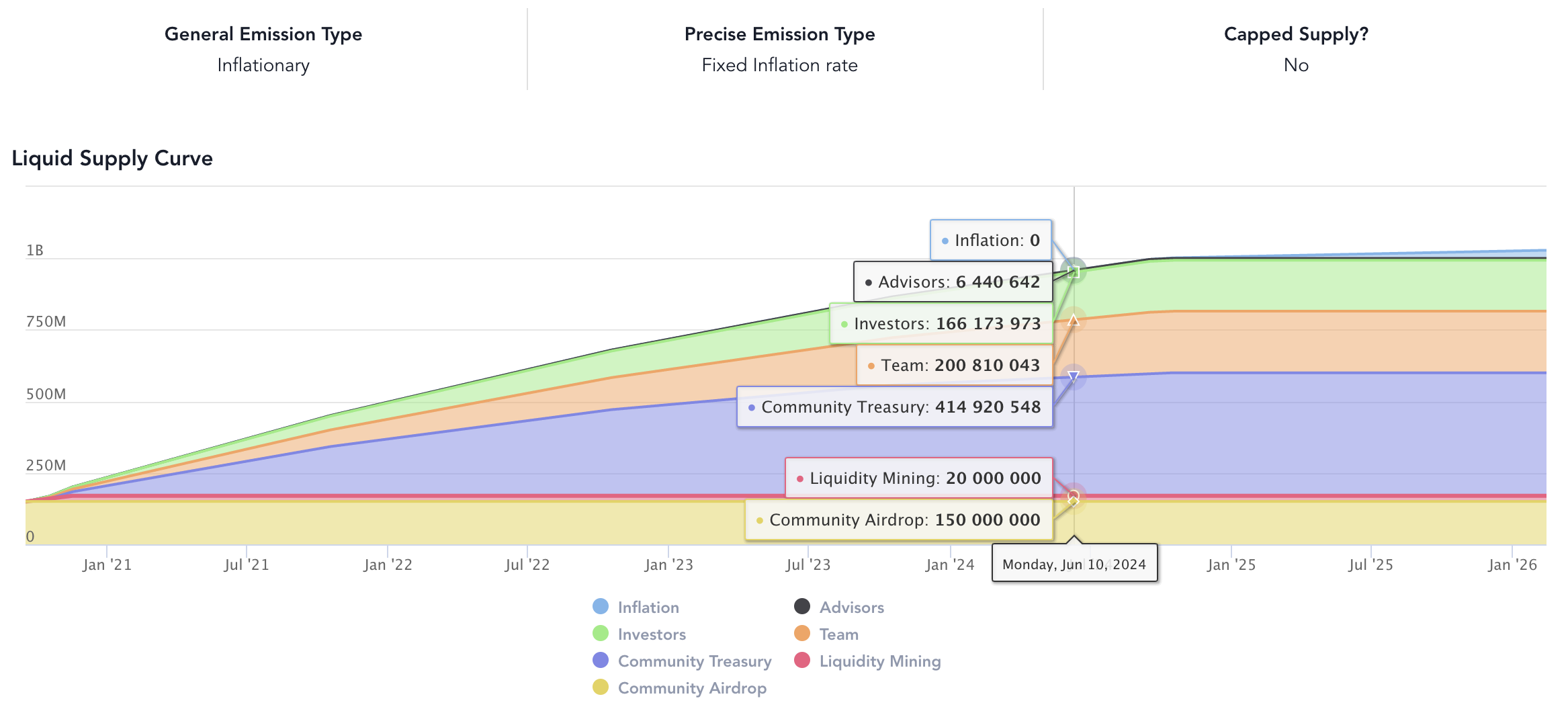

Other crypto assets have much more complicated supply schedules. Below is the supply schedule for UNI, the native crypto asset for the Uniswap decentralized exchange:

The supply is uncapped and inflationary. As you can see, there are at least six different type of key stakeholders and mechanisms for distributing the UNI token. We'll come back in a future article and look at these in more detail.

How are they used?

The governance and supply schedule are important to how a crypto asset is used.

From Cryptoassets:

For equities and bonds, the use cases are straightforward. Equities allow a company to raise capital from the capital markets via issuance of shares, while bonds allow a company to raise capital via the issuance of debt. Currencies are clear-cut in their use cases as well, serving as a means of exchange, store of value, and unit of account.

Commodities are where use cases can become more diverse. The use cases for metals or semiconducting agents changes as technology progresses. For example, silicon was once a forgotten element, but with the age of semiconductors it has become vital, causing arguably the most innovative valley in the world to be named after it (though there is no physical silicon to be taken from the ground there).

Since crypto assets are software, their use cases change and grow as the technology evolves. In some ways, they are like silicon.

Bitcoin is relatively straight forward in its use case. It is a digital store of value similar to gold. That said, there are non-monetary uses of Bitcoin in digital identity, and Bitcoin is also being used as a platform to build layer 2 monetary solutions like the Lightning Network.

Ether is less straight forward, since it is required as computational gas to perform operations within the decentralized Ethereum "world computer", but also appears to have store of value characteristics and can be staked within the Ethereum ecosystem to generate yield.

The range of use cases for other crypto assets is very broad, and because they are software, their use cases evolve and are more dynamic than any asset class before.

What is the basis of value?

Crypto assets derive their value from utility value and speculative value.

Utility value is what the asset is used for. In the case of Bitcoin, BTC is a store of value asset like gold, and so would be valued based on supply and demand like other C/T or liquid store of value assets. YFI, the native asset of the decentralized finance application Yearn, is a capital asset that earns fees for optimizing yield and would be valued based on the net present value of a discounted stream of cash flows like other capital assets. In the case of Ethereum, valuing ETH would require applying supply and demand analysis to the portion of ETH held as a store of value and the portion held to pay "gas" fees to use Ethereum, and capital asset techniques to the portion of ETH staked to generate yield.

Speculative value is the hypothetical value investors see in an asset based on projected growth and expected future utility value. This value is very similar to the hypothetical value of an early stage startup and is evaluated as we've discussed in the past.

As a crypto asset matures, its value will converge on its utility value. Investing in emerging crypto assets is a bet and arbitrage on the state of the world today vs the state of the world tomorrow.

Path to maturity

Bills of exchange were very illiquid before bankers in Antwerp created the Antwerp Bourse, the world's first money market. Shares of the world's first joint stock corporation, the Dutch East India Company, were very illiquid until the Amsterdam Stock Exchange, the world's first stock exchange, grew up around the informal market that developed to trade Dutch East India Company shares.

A similar process is taking place with crypto assets, as many crypto asset exchanges have emerged and are beginning to support the liquidity and trading profiles you might expect of more mature asset classes.

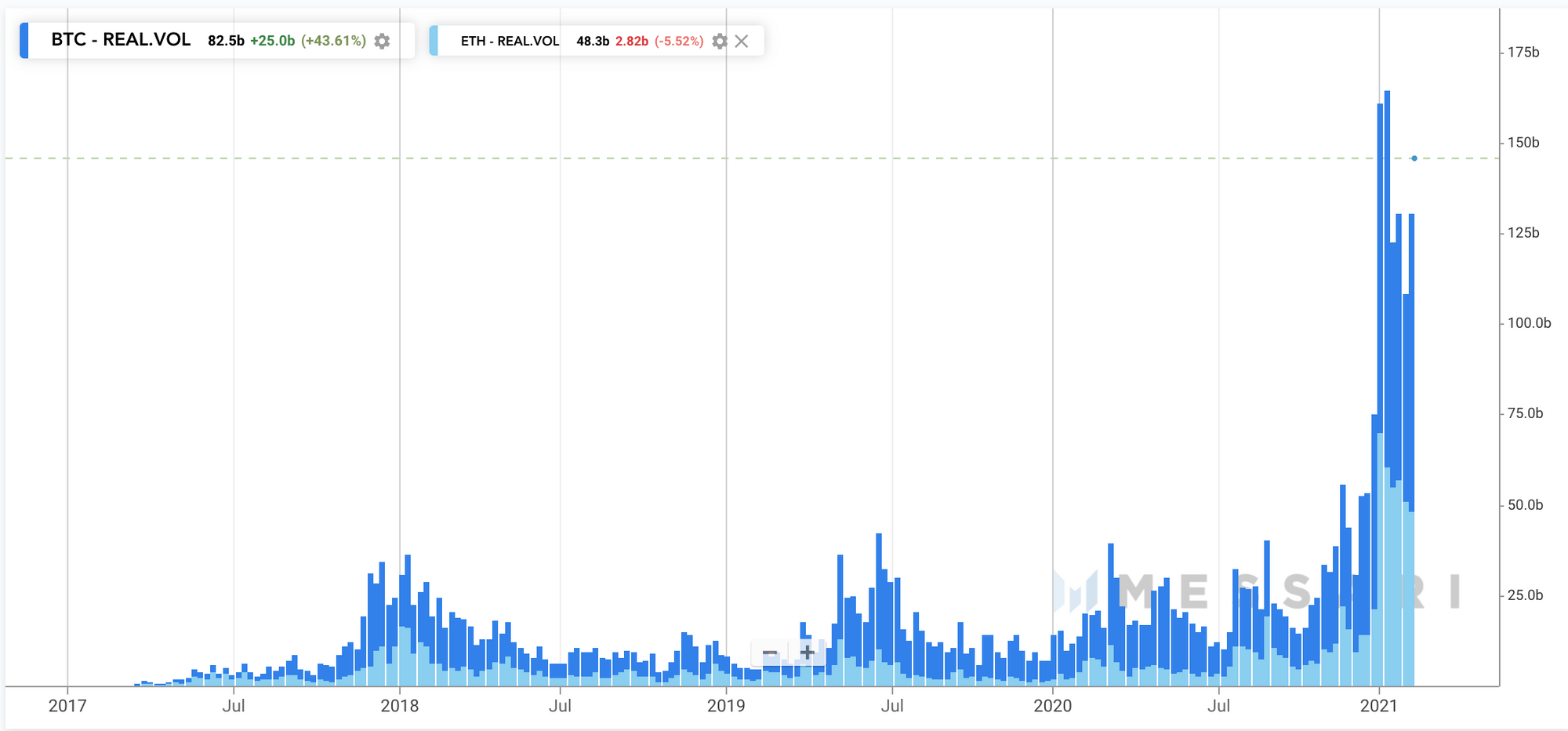

Trading volumes for both BTC and ETH are steadily increasing and have roughly tripled their typical 2020 volume range in 2021:

The number and diversity of trading pairs in crypto also continues to increase. Binance, the world's largest centralized exchange by volume, lists 1,383 trading pairs. Coinbase Pro, the 4th largest centralized exchange by volume, lists 133 pairs. Uniswap, a decentralized exchange, lists a staggering 30,290 pairs.

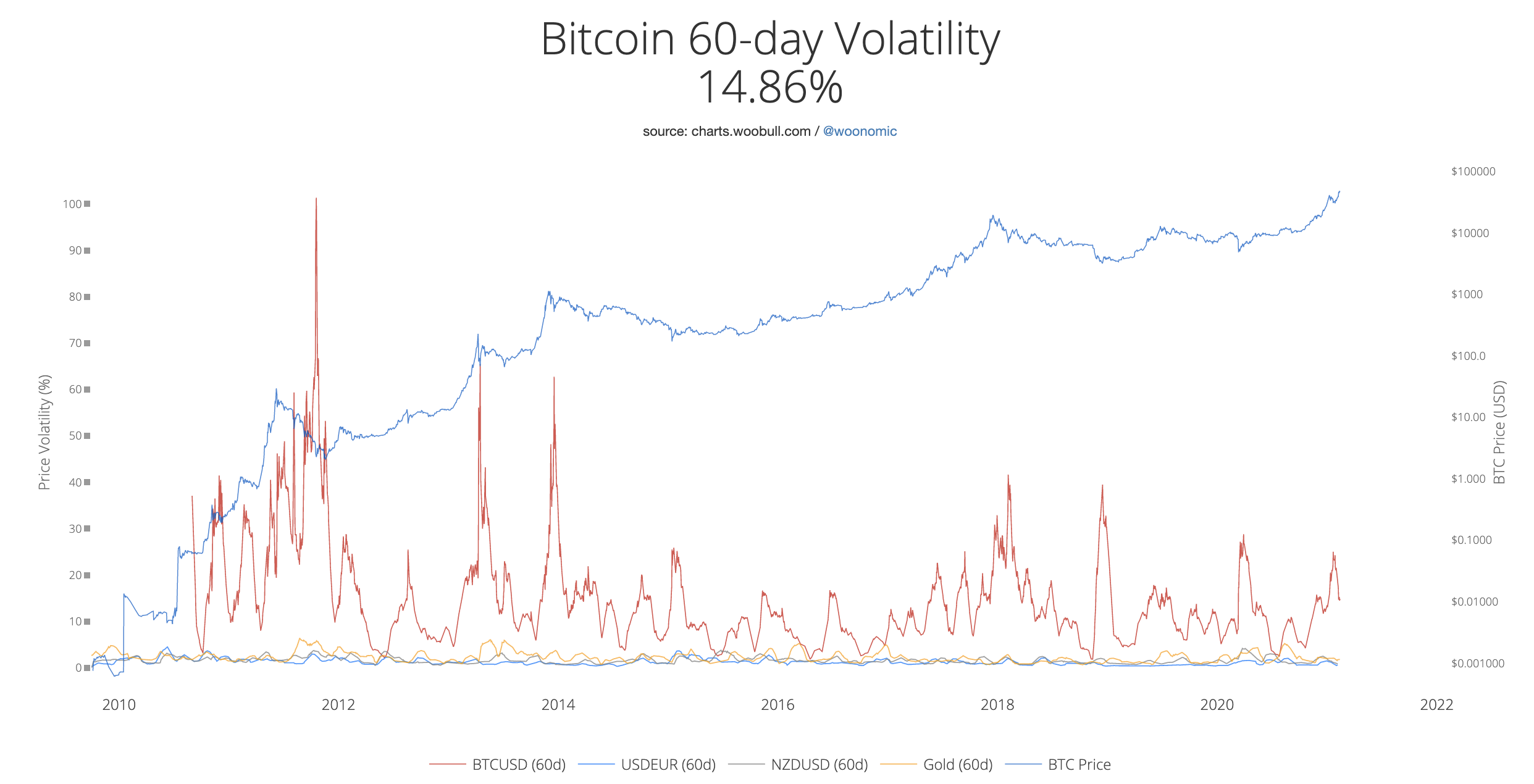

Bitcoin is still much more volatile than more traditional assets. A downward trend in volatility is what you would hope to see in a maturing crypto asset. This is an area where crypto assets need a lot of improvement. But when you consider that crypto assets are today similar to startups, their volatility is less surprising.

Finally, while nascent, crypto regulation has emerged that further legitimizes crypto as an asset class. On July 23, 2020, the U.S. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) confirmed that safekeeping and custody of cryptocurrency and crypto assets are traditional banking services and, therefore, are permissible activities for national banks and federal savings associations. On January 4, 2021, the OCC further confirmed that federally chartered banks and thrifts may participate in independent node verification networks and use stablecoins for payment activities.

Crypto is still young and has a long way to go. But these are positive and necessary steps on the path to maturity.

Conclusion

It might seem like crypto assets are unusually volatile or subject to market manipulation. In reality, they are on the same evolutionary path that new asset classes have gone through over hundreds of years on the path to maturity.

Crypto assets are subject to the same destabilizing factors that all asset classes have dealt with: speculation of crowds, "this time it's different" thinking, Ponzi schemes, misleading information from issuers, and attempts at market cornering.

For a good perspective on each of these situations in the context of crypto, I recommend reading Cryptoassets. Just keep in mind that the book is several years out of date in a space that is moving incredibly fast.

Did you like this article? Subscribe now to get content like this delivered free to your inbox. Learn more about what I do: https://andyjagoe.com/services/

- Cover photo by Inês Pimentel

- Nik Bhatia, Layered Money, 2021

- Chris Burniske and Jack Tatar, Cryptoassets: The Innovative Investor's Guide to Bitcoin and Beyond, 2017.

- Chris Burniske and Adam White, Bitcoin: Ringing the Bell for a New Asset Class, ARK Invest, 2017.

This newsletter is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. This newsletter may link to other websites and certain information contained herein has been obtained from third-party sources. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, Software Eats Money has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation.

References to any companies, securities, or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services.

Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Content in this newsletter speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others.